Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forest

System: Palustrine

Subsystem: Forest

PA Ecological Group(s): River Floodplain

Global Rank:GNR

![]() rank interpretation

rank interpretation

State Rank: S4

General Description

This community is primarily associated with intermediate and smaller tributaries on low to intermediate elevation islands and terraces. The presence of several tree species with low to moderate flood tolerance suggests the substrate is sufficiently coarse and the flow is sufficiently rapid to prevent significant development of anaerobic soil conditions. The substrate is saturated or inundated annually from less than a week to as long as three months each year (typically more than 7 weeks each year). The substrate is usually coarse sand and gravel, often with inclusions of cobble-lined scour channels.

This community is clearly dominated by sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) in the forest canopy, but usually has significant cover of one or more other hardwood species. Typical canopy associates include sugar maple (Acer saccharum) on smaller tributaries, silver maple (Acer saccharinum), and river birch (Betula nigra). The sub-canopy may be sparse to moderately dense, consisting of canopy species as well as hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana). Typical shrubs include spicebush (Lindera benzoin) and smooth alder (Alnus serrulata). On sites with a closed canopy, jewelweed (Impatiens spp.), clearweed (Pilea pumila), false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), wild germander (Teucrium canadense), jumpseed (Persicaria virginianum), Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), and green-dragon (Arisaema dracontium) are common. With a more open canopy, goldenrods (Solidago spp.), deer-tongue grass (Panicum clandestinum), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia), and riverbank wild-rye (Elymus riparius) dominate the herbaceous layer. The shrub and herbaceous layers are often heavily impacted by non-native plant species such as multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), Morrow’s honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii), common privet (Ligustrum vulgare), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea), Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), dame’s-rocket (Hesperis matronalis), and garlic-mustard (Alliaria petiolata).

Rank Justification

Uncommon but not rare; some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

Identification

- Found on low to intermediate elevation islands and terraces of intermediate and smaller tributaries of the Susquehanna and Delaware river basins

- The substrate is temporarily flooded from less than a week to as long as three months each year (typically more than 7 weeks each year)

- Clearly dominated by sycamore in the forest canopy, but usually has significant cover of one or more other hardwood species, usually river birch

- Influenced by high intensity flooding events

Trees

Shrubs

Herbs

- Jewelweed (Impatiens spp.)

- Clearweed (Pilea pumila)

- False nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica)

- Wood-nettle (Laportea canadensis)

- Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

- Ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris)

- Wild germander (Teucrium canadense)

- Green-dragon (Arisaema dracontium)

- Goldenrods (Solidago spp.)

- Wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia)

- Riverbank wild-rye (Elymus riparius)

- Bugleweed (Lycopus uniflorus)

* limited to sites with higher soil calcium

Vascular plant nomenclature follows Rhoads and Block (2007). Bryophyte nomenclature follows Crum and Anderson (1981).

International Vegetation Classification Associations:

USNVC Crosswalk:None

Representative Community Types:

Piedmont / Central Appalachian Rich Floodplain Forest (CEGL004073)

River Birch Low Floodplain Fores (CEGL006184)

NatureServe Ecological Systems:

Central Appalachian River Floodplain (CES202.608)

NatureServe Group Level:

None

Origin of Concept

Zimmerman, E., and G. Podniesinski. 2008. Classification, Assessment and Protection of Floodplain Wetlands of the Ohio Drainage. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Pittsburgh, PA. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Office of Conservation Science. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-973081-01-0., Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. 2004. Classification, Assessment and Protection of Non-Forested Floodplain Wetlands of the Susquehanna Drainage. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, Ecological Services Section. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-98337501.

Pennsylvania Community Code*

SE : Sycamore – (River Birch) – Box Elder Floodplain Forest

*(DCNR 1999, Stone 2006)

Similar Ecological Communities

Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forest is dominated by sycamore. River birch, which is often a canopy dominant of Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forests, is absent, or nearly so, in the Sycamore Floodplain Forest. Differences in soils, site hydrology, stream order and landscape position, and other ecosystem factors contribute to differences in species composition between the Sycamore Floodplain Forest and Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forest type associated with the Susquehanna and Delaware river basins.

Fike Crosswalk

None. This type is new to the Pennsylvania Plant Community Classification developed from river floodplain classification studies in the Susquehanna and Ohio River Basins. It is related to the Sycamore - (river birch) - Box-elder Floodplain forest concept in Fike (1999), now separated into two types to reflect the near absence of river birch in the Ohio Drainage.

Conservation Value

While this type itself is not rare in Pennsylvania, large contiguous forested floodplains along stretches of free flowing river are uncommon. Due to the widespread conversion to agriculture and development, large patches of floodplain forest are uncommon in Pennsylvania and hold high conservation significance. This community also serves as a buffer for sediment and pollution runoff from adjacent developed lands by slowing the flow of surficial water causing sediment to settle within this wetland.

Threats

Alteration to the frequency and duration of flood events and development of the river floodplains are the two greatest threats to this community statewide and can lead to habitat destruction and/or shifts in community function and dynamics. Non-native invasive plants may be equally devastating as native floodplain plants are displaced. Development of adjacent land can lead to accumulation of agricultural run-off and pollution, sedimentation, and insolation/thermal pollution.

Management

Direct impacts to the floodplain ecosystems (e.g., road construction, development, filling of wetlands) have greatly altered their composition, structure, and function region-wide. Further impacts that alter riparian function of the remaining areas should therefore be avoided. When development is unavoidable, low impact alternatives (e.g., elevated footpaths, boardwalks, bridges, pervious paving) that maintain floodplain processes should be utilized to minimize impacts to natural areas and plant and animal species within. Maintenance of natural buffers surrounding high quality examples of floodplain wetlands is recommended in order to minimize nutrient runoff, pollution, and sedimentation. Care should also be taken to control and prevent the spread of invasive species into high quality sites.

As floodplains are dependent on periodic disturbance, natural flooding frequency and duration should be maintained and construction of new dams, levees, or other in-stream modifications should be avoided. Activities resulting in destabilization of the banks or alteration of the disturbance patterns of the site should be avoided. Numerous landuse planning recommendations have been proposed to reduce the negative impacts of changing land use on riparian systems. These include protecting riparian buffer habitat, retaining natural areas in developed landscapes, compensating for lost habitat, excluding livestock grazing from riparian areas, providing corridors between riparian and upland habitats, avoiding constructing roads and utility lines through riparian habitat areas, and restoring degraded riparian habitat. Providing the river system some scope to maintain itself may be more cost-effective in the long run than attempts at controlling natural functions through human intervention.

Research Needs

Variations occur at ecoregional levels. Plot data collected during floodplain studies to characterize floodplain communities indicated that Sycamore Floodplain Forests differ significantly between different drainages, most importantly, river birch (Betula nigra) shares dominance with sycamore in the Susquehanna drainage. Differences in soils, site hydrology, stream order and landscape position, and other factors contribute to differences in species composition between this type, primarily found in the Susquehanna and Delaware river basins and the similar Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forest type associated with the Ohio Basin. There is need to monitor high quality examples of this community type.

Trends

Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forests were undoubtedly more common but have declined due to dam impoundments, human development, and farming; modification of the adjacent upland has further impacted the quality of this type. As this type requires high velocity flows, alteration of the natural flooding regime (duration and frequency) has most likely been the most critical factor influencing the quality and persistence of this type. The relative trend for this community is likely stable or may be declining slightly due to development; however, new alterations to river hydrology could result in significant changes to this type. High quality examples are most likely declining with invasion of exotic plant species, lack of recruitment due to deer browsing, and lack of periodic flooding events.

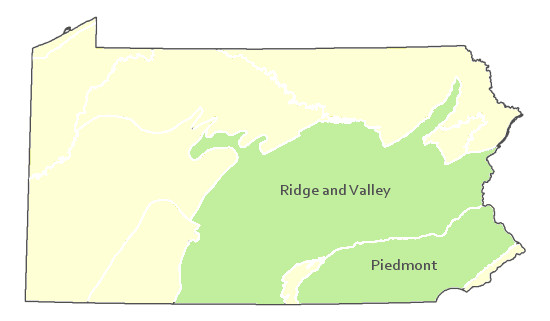

Range Map

Pennsylvania Range

Ridge and Valley, Piedmont

Global Distribution

Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Cowardin, L.M., V. Carter, F.C. Golet, and E.T. La Roe. 1979. Classification of wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, D.C. 131 pp.

Edinger, Gregory J., D.J. Evans, Shane Gebauer, Timothy G. Howard, David M. Hunt, and Adele M. Olivero. 2002. Ecological Communities of New York State. Second Edition. A revised and expanded edition of Carol Reschke's Ecological Communities of New York State. New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Albany, NY. 136 pp.

Fike, J. 1999. Terrestrial and palustrine plant communities of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Natural Diversity Inventory. Harrisburg, PA. 86 pp.

Khan, Nancy R., Ann F. Rhoads, and Timothy A. Block. 2005. Characterization and assessmant of the Floristic Resources in Evansburg State Park. Report submitted to DCNR, Bureau of State Parks.

Khan, Nancy R., Ann F. Rhoads, and Timothy A. Block. 2008. Vascular flora and community assemblages of Evansburg State Park, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 135(3): 438-458.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, Virginia. USA

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). 1999. Inventory Manual of Procedure. For the Fourth State Forest Management Plan. Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry, Division of Forest Advisory Service. Harrisburg, PA. 51 ppg.

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. 2002. Classification, Assessment and Protection of Forested Floodplain Wetlands of the Susquehanna Drainage. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, Ecological Services Section. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-993731.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2004. East Goshen Township Wetlands; Vegetation Inventory and Management Recommendations. Reoprt submitted to East Goshen Township, Chester County, PA.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2004. Lehigh Gorge State Park Natural Resource Inventory. Report submitted to DCNR, Bureau of State Parks.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2005. Jacobsburg Environmental Education Center Vegetation Inventory. Report submitted to DCNR, Bureau of State Parks.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2005. Lackawanna State Park Vegetation Inventory. Report Submitted to DCNR, Bureau of State Parks.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2008. Natural Areas Inventory Update, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Montgomery County Planning Commission, Norristown, PA.

Rhoads, Ann F. and Timothy A. Block. 2008. Vegetation of Ridley Creek State Park. Report submitted to DCNR, Bureau of State Parks.

Stone, B., D. Gustafson, and B. Jones. 2006 (revised). Manual of Procedure for State Game Land Cover Typing. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Game Commission, Bureau of Wildlife Habitat Management, Forest Inventory and Analysis Section, Forestry Division. Harrisburg, PA. 79 ppg.

Zimmerman, E., and G. Podniesinski. 2008. Classification, Assessment and Protection of

Floodplain Wetlands of the Ohio Drainage. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Pittsburgh, PA. Report to: The United States Environmental Protection Agency and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Office of Conservation Science. US EPA Wetlands Protection State Development Grant no. CD-973081-01-0.

Cite as:

Zimmerman, E. 2022. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Sycamore – Mixed Hardwood Floodplain Forest Factsheet. Available from: https://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/Community.aspx?=30019 Date Accessed: March 11, 2026